Rock and Roll to the U.S. Open: Explore the Visionary Mind of Derek Bryson Park, the Master of Turning Chaos into Spectacle

The air at the USTA National Tennis Center in Flushing Meadows, New York, always carries a kind of electricity that hums beneath the clatter of hard soles and the whisper of rackets through summer heat. The sound has its own weather, a pulse that belongs only to the U.S. Open. Years ago, before the retractable roofs and corporate suites, before celebrity boxes turned into cultural theater, a teenage boy stood behind the lines in that noise, unnoticed, small for his age, and waiting for a chance that wasn’t meant for him.

When the director of the ballboy pen waved off the CBS producer looking for a helper, the boy felt the sting of rejection cut cleanly into his resolve. However, that boy, Derek Bryson Park, would come to hold the keys to that very stadium. The same tournament that once turned him away would one day move at his command.

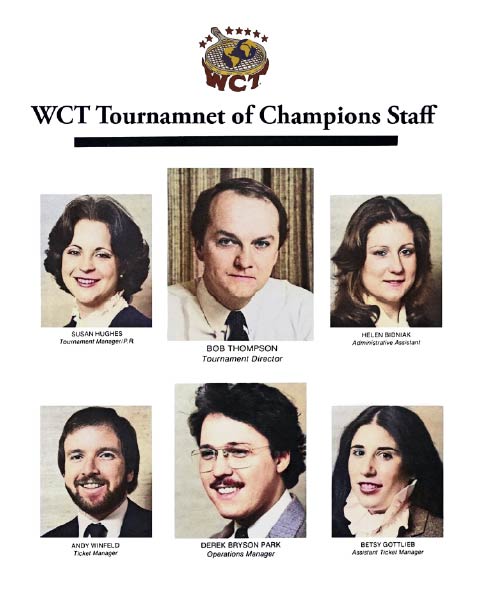

What followed is not the familiar story of a man chasing fame. Derek’s ascent through the most demanding corridors of American sport, from the U.S. Open to Lamar Hunt’s empire of championship tennis, to the Robert F. Kennedy Memorial Tournament, and finally into the colossal concert stages of Live Nation’s forerunner, was less a climb than a long choreography. His genius was not in invention, but in orchestration: the ability to make chaos obey rhythm.

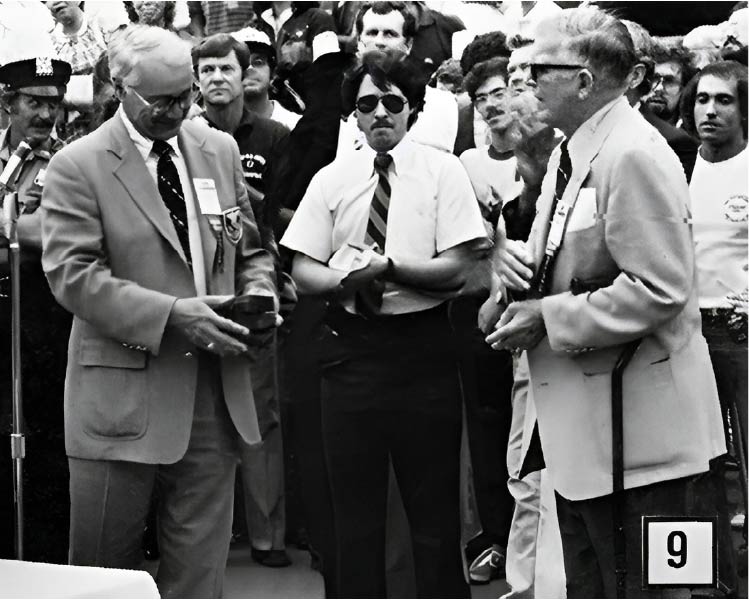

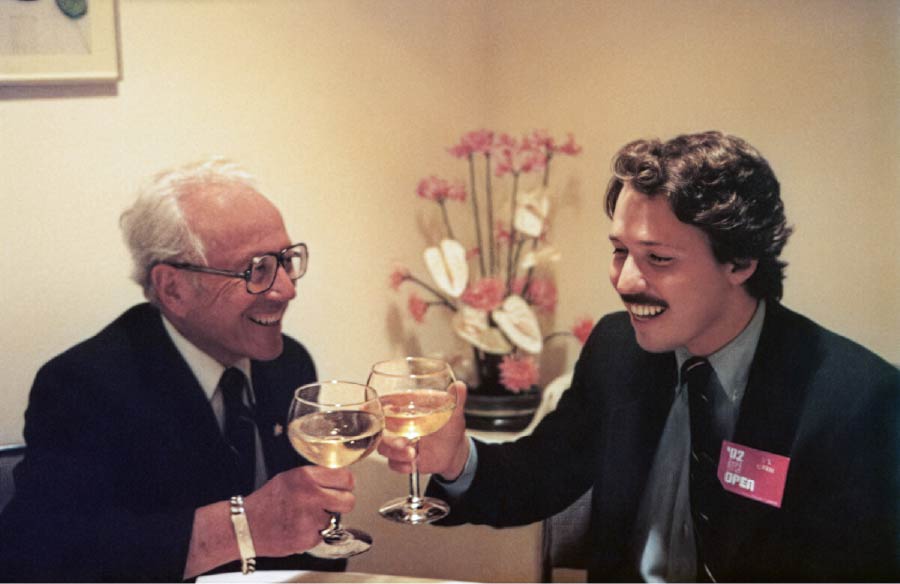

![[Left to Right] Operations Director, Derek Bryson Park; Tournament Chairman and President of the Interpublic Group of Companies [NYSE: “IPG”] J. Donald McNamara Presenting the Championship Trophy to American Tennis Star, Eddie Dibbs; Forest Hills Invitational, New York](https://visionarycios.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Left-to-Right-Operations-Director-Derek-Bryson-Park-Tournament-Chairman-and-President-of-the-Interpublic-Group-of-Companies-NYSE-IPG-J.-Donald-McNamara.jpg)

The Boy Who Quietly Rewrote the Rules

It began at thirteen, a moment in history so humble it could have dissolved without record. A boy fetching coffee and sandwiches for Howard Reifsnyder and Bob Daly, titans of CBS Sports. But Derek turned the errand into an apprenticeship. By sixteen, he was a fixture in the broadcast compound, and by nineteen, he was being written about as the young Director of Operations for the U.S. Open Championships, a role that in scope rivaled the managerial demands of small cities.

The Open, held at the USTA National Tennis Center in Flushing Meadows, New York, was and remains a machine of almost military precision: hundreds of thousands of spectators over three weeks, hundreds of athletes, a small army of contractors, police, medics, vendors, and press. Derek commanded it all with a calm, nearly mathematical poise. He negotiated labor with ticket takers and ushers’ unions, managed budgets with the vigilance of an auditor, and oversaw security in coordination with the New York Police Department, the Secret Service, and at times even the Federal Aviation Administration.

Planes from LaGuardia and JFK, roaring so near that their engines rattled glass and patience alike, had to be rerouted mid-competition, a logistical feat achieved through persistent negotiation with federal authorities. He made the skies quieter so the game could breathe.

The Open was not just a sport; it was a spectacle and civic theater. And Derek understood it as such. He viewed operations as choreography, every limousine, every anthem, and every floodlight contributing to a larger rhythm of grace and timing. He didn’t simply manage events; he composed them.

In the evenings, when the courts were swept clean and the crowds shifted for the night sessions, Derek remained behind the scenes, overseeing “sweeps,” ensuring that transitions happened seamlessly between day and night. It was in these quiet, unseen hours that leadership revealed itself: not in applause, but in the absence of mistakes.

Where Authority Was Earned, Not Announced

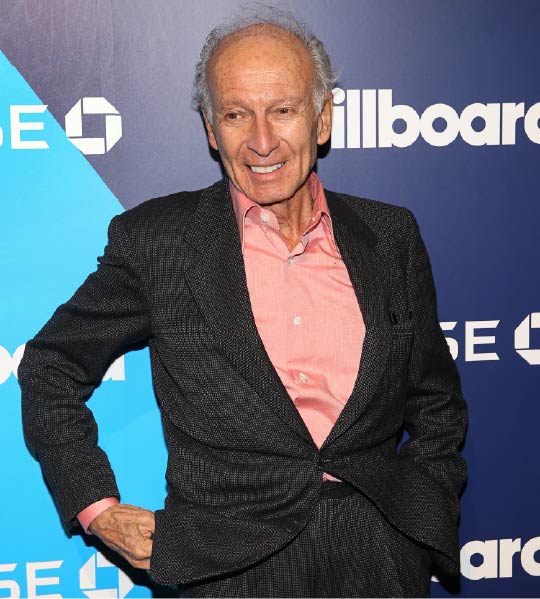

Leadership, as Derek practiced it, was an act of invisible control. He never raised his voice and rarely smiled. Those who worked under him, hundreds and often twice his age, respected him not for authority claimed, but authority earned. “I grew a mustache so they’d take me seriously,” he quotes. “And I stopped smiling because I had to look older than I was.”

He hired FBI agents to run security, not because it sounded impressive, but because they understood precision and discretion. He recruited medical volunteers, accountants, maintenance crews, and carting contractors with the same discernment. Every department was a system, and he was the architect ensuring no system failed under strain.

When the Open drew presidents and vice presidents, from Nixon to Clinton, Derek coordinated personally with the Secret Service, walking them through the perimeters, calculating sightlines against potential sniper vantage points. For him, “security” was never a word on a plan; it was an ethic, the guarantee that chaos, however inevitable, would never reach the court.

Behind the glamour of each match was an infrastructure of discipline, the lights, the air, the sound, the human choreography that makes an event seem effortless. Derek understood that to the public, “effortless” is the highest compliment, and the hardest thing to engineer.

![[Left to Right] International Tennis Star Ivan Lendl; Derek Bryson Park; and Co-founder of World Champion Tennis [“WCT”]; Founder of the American Football League (“AFL”); and Founder and Owner of the Kansas City Chiefs of the National Football League (“NFL”), Lamar Hunt](https://visionarycios.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Left-to-Right-International-Tennis-Star-Ivan-Lendl-Derek-Bryson-Park-and-Co-founder-of-World-Champion-Tennis-WCT-Founder-of-the-American-Football-League-AFL.jpg)

The Moment Ambition Slipped and Precision Caught It

From the courts of New York, Derek’s command extended southward to Texas, where visionaries still made sport by hand. Lamar Hunt, heir to oil wealth, creator of the Super Bowl, and founder of World Championship Tennis, recognized Derek not as a functionary but a strategist.

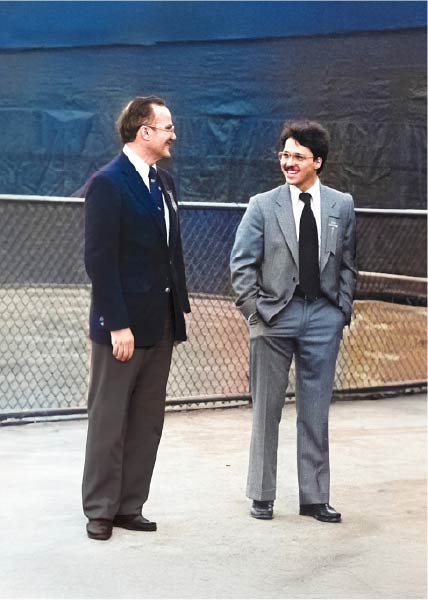

Hunt’s empire operated like a constellation, a network of events that stretched from the WCT Tournament of Champions to the Forest Hills Invitational to the WCT World Doubles in London. These were not mere tournaments; they were showcases of American ambition. Derek, barely in his twenties, became Hunt’s Director of Operations, responsible for building order within the dreamscapes of a man who had already invented the very concept of the Super Bowl.

At Forest Hills, Derek managed crowds that overflowed the stadium, overseeing logistics for matches that drew television audiences across continents. In Hunt, he found a mirror: a man who believed that sport could be both business and art. And in Derek, Hunt found the executor who could turn vision into motion, translating ideas into blueprints, then blueprints into sound and light.

The golden trophy Hunt designed was a 14-karat solid-gold racket weighing around thirty pounds and nearly slipped from his hands on live television. Derek caught it just in time. “It was heavier than ambition,” he’d later quip. The image of a young man steadying a trophy and a moment might as well have been the portrait of his career.

A New Stage: The Davis Cup Quarterfinals

As fortune would have it, Derek’s journey took another exhilarating turn when the United States Tennis Association invited him to step into the role of Director of Operations for the Davis Cup Quarterfinals, a prestigious clash between the United States and Czechoslovakia. The moment was electrifying, as it featured three of the four greatest players in the world: the indomitable John McEnroe, the fierce Jimmy Connors, and the legendary Ivan Lendl.

Once again, the national tennis center in Flushing Meadows, New York, served as the grand stage for this epic showdown. Derek was tasked with ensuring that every operational detail, from the seating arrangements and media coordination to the athletes’ logistics and security, was executed flawlessly.

The event demanded precision at the highest level, and Derek delivered it with the same composure and mastery that had come to define his work. For him, it wasn’t merely another tournament; it was a living symphony of movement, tension, and grace, one that reaffirmed his lifelong ability to transform complexity into harmony.

The Quiet Steward of a Nation’s Memory

Between tennis empires and televised arenas came a quieter task, one imbued with the solemnity of history. After Robert F. Kennedy’s assassination, the Kennedy family established the Robert F. Kennedy Memorial Pro-Celebrity Tournament, administered through the Park Foundation (unrelated to Derek, though an irony not lost on him). The foundation’s executive director, Steve Smith, the brother-in-law of both President John F. Kennedy and Senator Robert Kennedy, oversaw the event.

It was, by design, a convergence of politics, philanthropy, and sport, a stage where grief and grace intertwined. Derek managed the tournament’s operations, reporting directly to Smith and working in proximity to Senator Edward “Ted” Kennedy, whose locker stood only a few feet from his own. The event’s purpose was to celebrate the Kennedy legacy through athletic camaraderie and charitable cause, and it demanded from Derek the same precision he brought to the U.S. Open, only now tempered by reverence.

In a time still shadowed by political tragedy, Derek’s leadership offered calm and an assurance that even the most emotional of public spectacles could retain its dignity. It was leadership in the service of memory.

When Precision Met Performance and a City Held Its Breath

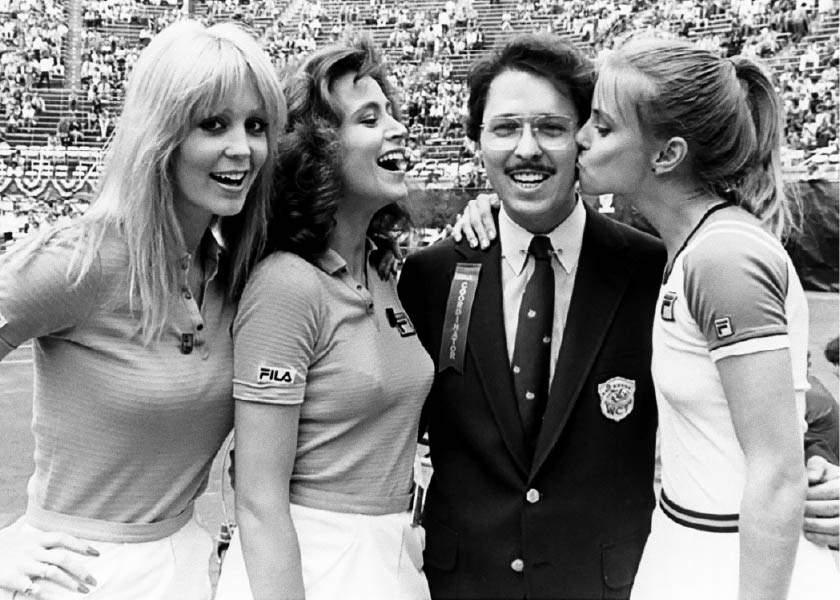

If the U.S. Open and WCT taught Derek the mechanics of movement, the concert world tested his endurance. Ron Delsener, founder of RD Productions, later Live Nation Entertainment, recruited him as Facility Manager, a role that required translating the rigor of sports operations into the unruly theater of rock and roll.

The scale was staggering. Derek found himself managing concerts for legends whose names now form a pantheon of American music: Frank Sinatra, James Taylor, Donna Summer, Linda Ronstadt, Joni Mitchell, Barry Manilow, The Boomtown Rats, Milton Berle, Ethel Merman, and Sammy Davis Jr. The performances ranged from intimate arenas to Central Park itself, the latter swelling to nearly half a million people for a James Taylor concert under the patronage of Gloria Vanderbilt.

The event remains, to this day, one of the largest public gatherings in New York City’s history. Derek orchestrated it with the same precision he brought to the U.S. Open, from sanitation to stage lighting, from security to crowd flow. The mayor’s office called it “an impossible success.” To Derek, it was simply another form of choreography and perhaps, a stadium by another name.

Working concerts was not glamorous. The artists were mercurial; the logistics unforgiving. But Derek, unflappable, approached each event with quiet command. He understood that leadership was not about being seen. It was about making others visible, the players, the performers, the audiences, the moment itself. His talent lay in removing friction from experience, so that only the brilliance of others remained.

The Stadium Was Never a Place, It Was His Principle

By the early 1980s, Derek had become something rare in American sports and entertainment, a figure who moved easily between both worlds, bringing with him a standard of discipline few could match. When he finally stepped away from the arena in 1982, he was still called back for two consecutive years to train his successors, a testament to trust that cannot be inherited, only earned.

The men he trained were older, the systems more complex, yet no replacement fully replicated his instinct for balance, an ability to blend order with humanity. “It takes a year to prepare for a twenty-one-day event,” he would say. “And a lifetime to learn how not to panic.”

In the years that followed, as Derek’s career turned toward corporate and public service, the echoes of those arenas remained in the cadence of his planning, in his reverence for structure, in his patience with chaos. The stadium, it turned out, was less a place than a principle: a living model of what happens when responsibility meets imagination.

Invisible Hands, Enduring Legacy

History tends to immortalize the faces on the podium, the champions, the entertainers, and the celebrated. But behind them, in the scaffolding of every triumph, stand the unseen architects who keep the machinery alive. Derek Bryson Park belongs to that lineage of invisible excellence.

He never claimed the platform; he built it. He never sought the camera; he made sure it had power. He never chased applause; he made sure it could be heard.

His life in sport is not a story of ambition rewarded, but of responsibility performed, the patient and exacting leadership that keeps great institutions from collapsing under their own weight. Whether at Flushing Meadows or Forest Hills, under the gold lights of Madison Square Garden or the open sky of Central Park, Derek’s fingerprints exist in the unseen perfection of the moment that works.

Leadership, in his world, was not about commanding attention. It was about earning silence. The silence that comes when a vast operation runs so flawlessly that no one thinks to question how.

And in that silence, the hum of the stadium returns, steady, sure, and eternal, carrying the invisible signature of the man who once stood, small and overlooked, behind the baseline, already imagining how to make the whole thing move.